FruitTrop Magazine n°244

- Publication date : 3/11/2016

- Price : Free

- Detailled summary

- Articles from this magazine

The world fresh pineapple market is one of uncommon simplicity. The overproduction in 2014 drove many producers out of business. Consequently, the world supply, especially from Costa Rica, has decreased, with the help of the impacts of major climate vagaries. Since then, the supply/demand balance has returned to an optimum level. World prices have picked up. Yet, barring a policy of differentiation, this cycle of climbing prices will inevitably be followed by a cycle of falling prices, since good economic returns have once more encouraged would-be producers.

As keen sailors will know, fierce squalls end in gentle rain. This is a good parallel for recent developments on the world fresh pineapple market, where the usual sluggishness has given way to euphoria. A relatively moderate reduction (- 12 %) in volumes brought to market by Costa Rica in 2015 helped the import price bound upward. Yet the potential and production capacities are still in place, and the comeback will arrive, if it has not already. The infernal cycle will resume with full force to destroy added value, and the pineapple market will return to the doldrums once again.

Creative destruction, the concept dear to Joseph Schumpeter, is illustrated perfectly on this market, at least in its destructive phase. The following phase, value creation through innovation, will need to wait its turn. It is not since the mid-1990s that any innovation has been seen in this industry. True, it was a major one, with the market standard variety Smooth Cayenne, from Côte d’Ivoire, being replaced by the MD-2 variety produced in Costa Rica. This varietal conversion, accompanied by other factors for success (a monolithic and highly efficient industry organisation, stable visual quality, reliable intrinsic quality, etc.), enabled a pineapple consumption boom. We should recall that European consumption went from approximately 200 000 tonnes in the early 1990s to the absolute record of 938 000 tonnes reached in 2014. The US market did even better. Starting from a lower point (approximately 120 000 tonnes in the early 1990s), it is still clinging to a record level of over one million tonnes. Whether in the United States or Europe, this volumes growth dynamic is to this day unprecedented in the world of fruits and vegetables.

While the growth engine is idling in the United States (sales growth 2 % in 2016 according to our projections), on the other side of the Atlantic sales are down steeply. After a catastrophic 2015 when 11 % of the volume disappeared, i.e. all of 100 000 tonnes, the size of the European pineapple market should shrink further in 2016 (- 1 %), according to our forecasts. The sales level should equal that of 2007, sliding backward by one decade.

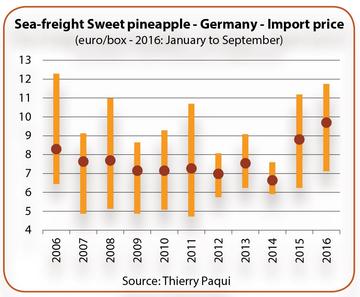

We can read this unprecedented downturn in at least two ways. The first lies in looking only at the falling consumption level and lamenting the downturn in the pineapple’s penetration rate in European households. The second way involves analysing product volume and value jointly. For the past two years (2015 and 2016), it has to be recognised that the pineapple market has exhibited highly orthodox workings. The product value at the import stage has evolved in inverse proportion to the increasing volumes. We can measure this perfect consubstantiality between price and volume at the same time on both big markets, the US and EU. As the analysis of the 2015-16 campaign proposed by Thierry Paqui shows later on in this dossier, after a low point reached in 2014 at 6.6 euros/box (MD-2 variety into the EU), barring a commercial catastrophe at the end of the year, the average import price in 2016 should exceed 9 euros, i.e. an increase of nearly 50 %. It was in 2015 that the curve reached the inversion point. We should recall that in 2014 volumes sold broke records, with nearly 940 000 tonnes, and that 2015 brought a big ebb, of around 100 000 tonnes. This provides a powerful and unambiguous demonstration that the destruction of value is directly linked to the increase in volumes. We can even estimate, from the data of the past decade, the theoretical potential fall in the average annual price. If volumes on the market increase by 10 %, we potentially get a fall of more than 3 % in the annual import price.

In the United States, where volumes have stabilised at their highest level (more than one million tonnes) for three years, the causes are producing the same effects: prices, estimated by means of import unit value, are rising half-heartedly. In view of the price dynamic, the market is saturated at above one million tonnes for the United States, and 850 00 tonnes for the EU. Further volumes can be absorbed only by a fall in prices.

To finish on this point, the pineapple market looks just like that of an ordinary industrial consumer good. Barring serious climate vagaries, the well-known agronomic techniques enable multi-annual production scheduling. The supply comprises practically a single variety: MD-2. One source, Costa Rica, supplies 87 % of the EU’s consumption and 82 % of US consumption, i.e. the two main markets. The sole differentiation lies in terms of quality. While at the export and import stages, the qualitative differences are sometimes striking, they fade toward the downstream part of the chain. Although this is less true in periods of under-supply, we are a long way from a quest for excellence within the supermarket sector. Pineapple shelves in Europe are often eye-catching, but for the wrong reasons: repulsive fruits, with a green-brown coloration, withered crowns and at an advanced stage of maturity, to the delight of small flies, and sometimes even emitting an aroma of rotten fruit. Such situations are not uncommon, especially in small shops. If on top of that we take into account that the pineapple is not easy to prepare, retail deserves congratulations for being able to sell such large quantities!

So differentiation is the sole remedy for this depressed and depressing market. And there have been no new developments on this front. There are rumours, never with any commercial follow-up, announcing the launch of a new, more coloured, tastier, variety; more this, that and the other... Except that there are no developments on the horizon. To fill the gap, there is even talk of a new MD-2 variety, a sort of return to the Costa Rican Sweet sources of the 1990s, or 2000s. They are trying to regenerate the Smooth Cayenne. Malaysia, unknown on the big import markets, is promoting the local clone, the Sarawak pineapple. A Brazilian breeder has announced two new accessions: Cesar and David. The Philippines are promoting their new pineapple: the Super Sweet Snack Pineapple. Ghana, like the Dominican Republic, is advocating the use of a new MD-2 variety, etc. This may seem like an innovation race, but it all seems to be going nowhere; they are either rehashing old ideas or erring into fantasy. Nothing very serious is emerging. We are waiting for a big operator to pull out from under its hat, or indeed from its genetic enhancement programme, an improved or different variety, one that is able, beyond a niche market (air-freight pineapple, Smooth Cayenne, Sugarloaf or Victoria), to restore distributor and consumer interest in this fruit.

Others are going back to the root of all things in agriculture: complying with good agronomic practices. Older readers will recall that, in the 1990s, the Ivorian pineapple empire fell because it failed to respect the physiological stage of the fruit. Bending the product to the constraints of transport and the market invariably leads to a general fall in quality, adversely affects the value level, and in extreme cases, deters consumers from the product. Certain operators, who have control of their supply, have committed themselves to this differentiation approach with relish. True, this is nothing amazing; after all it is the minimum that we can expect from a fresh fruit professional, but it is effective. What ultimately counts, unfortunately, is not the absolute quality of the product but the fact that it is better than the next one. Downward levelling is a value earner for good professionals. That is at least one positive effect from this modern malaise.

For a few years now, operators have been able to revitalise or maintain pineapple demand thanks to on-the-shelf cutting and to the pre-prepared fresh segment. This is a very effective way of cleaning up this fruit’s poor image, with its laborious preparation and deteriorated quality on the shelf. It is also a way of boosting value for the sector, since the retail prices per kilo climb steeply the closer you go toward this pre-prepared fresh segment. Yet the service provided seems to be popular, and furthermore it brings this fruit into the world of snacking and packed lunches, where the biggest pockets of growth are. And this will remain the case as long as consumers are unconcerned at the price per kilo they are paying.

That’s all in terms of the marketing side. Let’s get back to developments by the big suppliers. At first glance, nothing is changing. Costa Rica holds 82 % and 87 % market shares in the United States and the EU respectively; almost a Soviet-style monopoly, so few crumbs remain for the rest. However, this situation does not seem to be as fixed as we might suspect. For example, if we look at its decline on the EU market by 100 000 tonnes between 2014 and 2015 (confirmed in 2016), certain weak signals can be detected. Not all the sources have suffered the same fate. Production difficulties have been focused exclusively in Costa Rica, and slightly in Panama. Other sources, namely African ones, have also cut their exports, but often at the strategic choice of the traditional operators. Conversely, and this is where things become interesting, certain sources have caught fire. There are four countries emerging in this category: Mexico, Ecuador, the Dominican Republic and Colombia. Mexico has made a surprising leap forward. It exports exclusively to the United States and its season comes later than Costa Rica’s. If the trend persists in 2016, it will have a flow of nearly 100 000 tonnes, i.e. 9 % of the US market. Among the older newcomers, Ecuador is also sparking. After a low point in 2013, i.e. a combined total of 20 000 tonnes on the two markets, it has resumed growth and will finish the year 2016 with nearly 37 000 tonnes (projection). Ultimately, the latter two sources belong to the category of micro-suppliers (between 6 000 and 8 000 tonnes each), but have very steep growth curves.

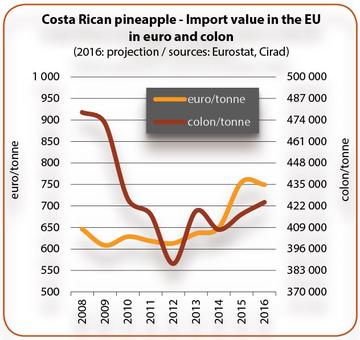

It would of course be a great exaggeration to think that it is the beginning of the end for the Costa Rican pineapple. The country leaves only a supporting role for the other suppliers to the international market, and this situation will not change in the near future. Yet since nothing is fixed for ever, the king could be dethroned, if we look at the recent developments in the sector. The Costa Rican professional association announced in late 2015 a production area of 38 000 hectares, as opposed to 45 000 ha one year previously. Indeed, the failure and shutdown of some plantations, which led to a distinct downturn in production in 2015 — which will persist in 2016 and doubtless into 2017 — show the economic difficulties that the industry must face. Profitability is no longer ensured by international prices, which have fallen greatly, and the financial returns are on the slide due to the strength of the local currency against the euro. Finally, certain operators have been forced out of the sector. This has helped re-balance world supply and demand, pushing prices upward. Returns to the producer have improved, though still insufficiently to restore the appetite among investors for this product, especially if they plan to sell it on the European market. The exchange rate, with the euro falling against the dollar and the colon, has mitigated the effects of the price boom on the European market. In 2016, the impact of the increase in international pineapple prices has above all favoured dollar zone shipments. Hence whereas for a very long time all observers were wondering whether the Costa Rican pineapple cost anything, such was the extent of planting, overproduction and its corollary, falling international prices, have prevailed over the madness.

After the economy, the second wall facing Costa Rican producers comprises both a technical and above all environmental impediment. Technical, since the United States is intercepting more and more insect-infected pineapple batches, and is even considering stricter import rules. Intensive production systems, of both banana and pineapple, entail a high sanitary pressure and therefore use of numerous chemical treatments. Besides the repercussions on human health and the environment, which we will return to shortly, these practices may in certain cases generate biological imbalances, causing the proliferation of pests which, due to the insecticide treatments for example, no longer have any predators. Hence the move toward more environmentally-friendly practices is also beneficial for plant and fruit health.

The need to safeguard the environment or halt its continuous deterioration is another threat weighing down the sector. We talk about it every year, and every year new scandals appear. You will recall the phytopharmaceutical products found after analysis in humans, animals and river water of the villages neighbouring certain production zones. In July 2016, the realisation seemed to have been materialised by a ban on extending pineapple cultivation. At any rate it applied to one district, Los Chiles, in northern Costa Rica (Huerta Norte region: 47 % of surface areas), which imposed a moratorium on expanding surface areas dedicated to the pineapple. The scope of this decision is extremely narrow, yet it has a powerful symbolic content, and could create ripples.

Working conditions have also been in the limelight. Furthermore, an Oxfam report which appeared in 2016 is highly critical about the working conditions of the workers in the Costa Rican pineapple sector. For the sake of completeness on the subject, the report also singles out the attitude of European distributors, who through their policy of ever lower purchase prices, are forcing producers into crime. In short, the golden age of the Costa Rican pineapple is no more, and the model needs to be renewed. Margins for progress for the sector are based on good agricultural practices inspired by the principles of agro-ecology (or even organic agriculture), a product differentiation policy, management of volumes to regain economic margins for manoeuvre, and finally the application of minimum international social standards.

Differentiation as a bulwark against erosion of added value is a classic recipe which has proven its worth in all industries. The pineapple is no exception, though it involves relatively small volumes compared to the core range, i.e. sea-freight MD-2. These niche markets are centred on the Victoria pineapple (Reunion and Mauritius), the air-freight Smooth Cayenne pineapple, amounting to more than 12 000 tonnes (Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Benin, etc.), and also the air-freight Sugarloaf (Benin). Here too, care must be taken not to corrupt the segment! Alerts over excessive ethephon levels, for example, have been calamitous for Benin (see ethephon inset). The occasional overuse of this classic, near-magical remedy for the overly green coloration, not to consumers’ liking, corrupts the product and the production source. The pineapple, especially in the air-freight segment, is a top-end product, purchased and consumed by a demanding clientele. Africa has also carved itself out a choice place on this market, with operators structured vertically to give this segment all the attention it requires on a separate basis.

So will it last? There is no denying that the pineapple market has been one of the big successes of the fruit sector over the past two decades. Driven by innovation and flawless commercial organisation initially, it has forgotten the fundamentals, which has led to a crisis of overproduction as well as a general fall in fruit quality. The reduction of the supply, following producer withdrawals and climate vagaries, has automatically pushed up world rates since 2015. The very considerable improvement in economic returns to the producer, in Costa Rica as elsewhere, will provide renewed incentives. However, without being a perennial plant, the pineapple has a relatively long production cycle, especially if we include the preparations: preparing the land, irrigation, plant production, packing station, personnel training, etc. We can assume that 2017 could largely be spared a turnaround in the trend; but definitely not beyond then, since the factors for failure are already in place

Click "Continue" to continue shopping or "See your basket" to complete the order.